Leonard Baskin (August 15, 1922 – June 3, 2000) was a prominent, award-winning artist of the mid-20th century. Spanning the mediums of sculpture, printmaking, illustration, and graphic design, and founding Gehenna Press (1942–2000), his work captures the human figure in commanding and despairing portrayals. Through a commission from the National Park Service to illustrate a handbook, Little Bighorn Battlefield, Baskin’s interest and understanding of Native Americans and their history evolved. His series of lithographs convey a deep respect for the courage and wisdom of the Sioux mixed with an expression of the tragedy at the loss and betrayal they faced.

During a collection review, we identified several lithographs from Baskin’s series of Native Americans with damage that would be improved with proper paper conservation techniques and custom archival framing materials. These pieces exemplify the qualities of figurative printmaking for which Baskin was known.

Condition

“Sioux with Green Oval” arrived at the studio with discoloration in the shape of a crooked rectangle across the image of the piece. The disfiguring effects of mat burn and light strike were caused by improper placement and hinging of an acidic mat combined with non-UV filtering glazing, which then amplified deterioration when left in an inadequate environment for long-term storage. In this poor condition, the piece could not be displayed and took a significant hit to its desirability and value.

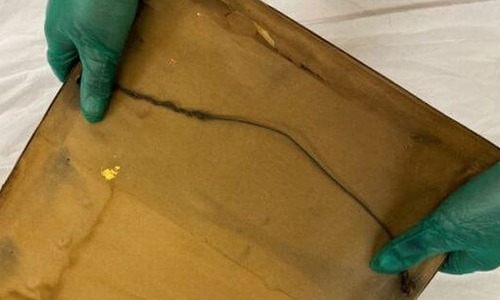

Upon closer inspection, we saw that the lithograph had minor layers of dirt and dust embedded into the surface and reverse. The sheet had a large crease in the lower-left corner and a smaller but more severe crease in the upper left corner. Other issues inherent to the piece included skinning on the face in the upper right quadrant, and that the edges of the paper had darkened significantly, likely from contact with the acidic wooden rabbet of a frame.

LEONARD BASKIN (1922-2000). Sioux with Green Oval; 1974; Color lithograph on paper, signed, numbered, dated, inscribed

“LBF 1974”; 29 11/16 in. x 41 7/16 in. Before (left) and after conservation (Right).

Treatment

“Sioux with Green Oval” was surface cleaned from both sides using soft mechanical methods. The sheet was then washed in buffered hydrogen peroxide aided by light with attention to the stained areas to reduce discoloration and stains and improve the pH balance. Select creases were supported from the verso using appropriate weight Japanese tissue. Lastly, the lithograph was dried and flattened between cotton blotters. The treatment successfully addressed the staining which also returned the original coloration and contrast of the colored ink. Now in presentable condition, the treated lithograph was then archivally framed for display.

LEONARD BASKIN (1922-2000). Crazy Horse; 1974; Color lithograph on paper, signed, numbered, dated, and titled in pencil; 29 9/16 in. x 41 ½ in. Before (left) and after conservation (right).

Baskin’s “Crazy Horse” lithograph came to the studio with varying degrees of discoloration throughout the sheet. There were significantly large creases on the upper right corner of the front and on the lower left edge. There was light soiling on the front and back. As well as handling dents and shallow creases throughout, and a fragment of pressure-sensitive linen tape adhered on the upper left corner of the verso.

Although these two examples look very different, the treatment of “Crazy Horse” was addressed with a similar approach as “Sioux with Green Oval.” In addition to surface cleaning from both sides, the tape and the related adhesive residue were poulticed, and then mechanically reduced. The sheet was also washed, creases repaired with Japanese tissue, and flattened. These techniques were ultimately successful in preserving the piece and highlighting the dark ink, broad expressive brush strokes, intricately layered, and fractured line quality for which Leonard Baskin was known.

1974 represented a change in Baskin’s career when he moved to England to work with a close friend and British laureate, Ted Hughes, with whom he collaborated on some thirty books that combined poetry with illustrations on themes of social justice. Baskin’s 1974 portraits were produced in the midst of the American Indian Movement, a time when the rights of Native Americans were being restored by the government. Because these lithographs are limited to an edition of 100, and they are wonderful examples of Baskin’s desire to highlight Native American history and heritage, their preservation is important. These two pieces were able to be successfully treated to address the sustained damage, however; the use of archival materials like UV filtering glass, ph-neutral rag matboards, and proper hinging techniques at the outset would have mitigated the necessity for the conservation treatment. With proper care and attention paid to how works of art are handled, stored, and framed the longevity of fine art may be ensured.

If you have questions about conservation or archival framing, please contact us at info@artifactservices.com.